SERMON - A User Guide to the Ten Commandments - 17th March 2024 - Glenboig Christian Fellowship

Click below to listen to the sermon being preached:

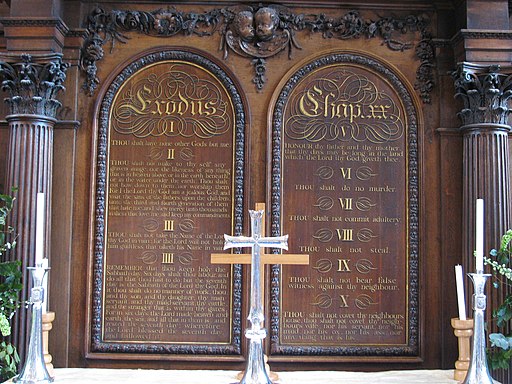

In the coming weeks and months I am (DV) going to be taking us on a journey through the Ten Commandments, the series of moral laws that God gave His people Israel as they travelled through the wilderness, in Exodus 20. For some of us, this will be a well-trod path, and for others this will be an adventure in uncharted territory. However, whether we like it or not, the Ten Commandments shape every aspect of our walks with God. At times we will cover some difficult teachings, but I pray that you will walk with me as we explore these things together, as we seek to cleave ever closer to God.

In order to fully understand the Ten Commandments, it is important that we remember a number of points. I had initially intended to explore the first Commandment today, but it is important that we understand and acknowledge these points for, without them, the Ten Commandments will just remain ink on the page. So instead, we will explore the first Commandment next month and, for now, will focus on these over-arching principles. Consider them a Ten Commandments’ User Guide – a framework to help us understand the Commandments as a whole, and to help us to explore each one individually. As I begin this series, I should also acknowledge the immense help that the Westminster Larger Catechism (1648) has been – not only did the Westminster Divines clearly put an inordinate amount of prayer and reflection into their works, but they also included their Scriptural proof texts which allowed me to, in turn, find the quotations and see what the Scriptures themselves said. For those of you who haven’t got a copy of the Catechism in the home, I would really recommend getting a copy – it is a well-worn book in our home and is often my first port of call to find a teaching and it’s Biblical basis. Of course, it is nowhere near as important as Scripture itself – in Presbyterianism we call it a ‘subordinate standard’ – but as long as we keep the Catechism in its place, subordinate to and explaining the Scriptures, it can prove immensely helpful. The sections covering the Ten Commandments are Questions 98 – 148 inclusive.

However, let us return to the Ten Commandments, and in particular to the pointers we should take note of if we are to understand God’s Commandments properly.

Firstly, we should remember that God’s Law is perfect – indeed the Psalmist writes that “The law of the Lord is perfect, reviving the soul.” (Ps. 19. 7) Perhaps this goes without saying, but without this bedrock belief we will soon flounder. Just as we believe that God is, Himself, perfect, it goes without saying that any laws that He has placed upon mankind will be perfect also. These laws, far from being there to restrict or in some way limit our lives, are there for our protection and to encourage our flourishing. In much the same way that a dog needs training in its puppy-hood, and without this training the dog will not have a happy life, so too we need boundaries in our life to protect us and help us enjoy the gift of life that God has given us. In receiving this Law, we cannot accept it in part, as though accepting Commandments 1,2,7,8 and 10 but rejecting the rest: James’ Epistle says “whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point has become accountable for all of it.” (2. 10) Now, of course, as Christians we know that we have failed in far more than just one point of the God’s Law, but this does not mean that we are not called to live lives in obedience to it.

Next we should remember that God’s laws do not concern the body, or the physical matter, only. Rather “we know that the law is spiritual” (Rom. 7. 14), concerning both body and the soul. This is why, in the Great Commandment, recited by Jews every morning, instructs the believer to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” (Deut. 6. 5) – our love for God should be no mere surface-level love, but something that engages all the senses, every fibre of our being.

Next we must remember that we may find the same sin condemned in more than one commandment. Take, for example, sexual related sins. The seventh commandment (“You shall not commit adultery” 20. 14), is the one traditionally associated with sexual sin, yet we read in Colossians that we must “Put to death… sexual immorality, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry” (3. 5), suggesting that these are not only adulterous sins, but also idolatrous ones. This just serves to reinforce the truth, that our sins have such consequences, and that what might start off as just one sin may lead us down many avenues best left untrod.

I mentioned earlier how helpful the Larger Catechism has been in preparing this series of sermons, so now seems a sensible time to share my first quotation from it. Our next pointer for better understanding of the Ten Commandments concerns the Commandments themselves. It says:

Where a duty is commanded, the contrary sin is forbidden; and, where a sin is forbidden, the contrary duty is commanded; so, where a promise is annexed, the contrary threatening is included; and, where a threatening is annexed, the contrary promise is included.1

What does this mean? Well, basically speaking, it means that every Commandment that says we mustn’t do something also implies that we must do something else, and every Commandment that says we must do something implies that we mustn’t do something else. It is not good enough, for example, to go around ‘not murdering’ if we have no respect for the sanctity of life, or the fact that it is a gift from God Himself. Jesus explains this in the Sermon on the Mount, where He says “You have heard that it was said to those of old, ‘You shall not murder; and whoever murders will be liable to judgement. But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother will be liable to judgement; whoever insults his brother will be liable to the council; and whoever says, ‘You fool!’ will be liable to the hell of fire.” (Matt. 5. 21-22)

Similarly, Jesus shows that the commandment to honour our fathers and mothers is far more than surface-level, and that while we are told to love and honour God, if we claim we cannot afford to care for our parents because we are giving money to God Himself, we are breaking that commandment (Matt. 15. 5). The law concerns what we do, and what we don’t do, what we think, and what we don’t think.

Next we have to understand that the Commandments highlight things that God forbids at any time – it is never right, at any time or in any situation, to murder, or steal. They also highlight things that are always our duty - it is always right, no matter the time nor the place, to honour father and mother, to keep the Sabbath day holy. Yet Jesus makes it clear in Matthew 12 that, to quote the Catechism, “and yet every particular duty is not to be done at all times.”2 Jesus explores this idea when addressing the Pharisees. The Pharisees had challenged Him and His disciples for plucking grain on the Sabbath, and Jesus says, “If you had known what this means, ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice,’ you would not have condemned the guiltless.” (Matt. 12. 7) Here Jesus is reminding the Pharisees that, even though the instructions to sacrifice to God are important and binding, at that moment the Pharisees needed to exercise mercy.

We have perhaps come across people who are so devoutly committed to following one law that they inadvertently break another. Perhaps we have seen it within the Church (people who hold fast to, say, God’s good and right commandment to keep the Sabbath day holy but, in so doing, fail to show mercy, or allow themselves to become puffed up). It is a difficult path to follow, but we have the Holy Spirit to help us if we just allow Him in.

Perhaps you have come across people who feel that the Commandments of the Old Testament have been superseded by Jesus. Not only have these people not read where Jesus says, “I have not come to abolish [the Law and the Prophets] but to fulfil them.” (Matt. 5. 17), but they have not read on to see how influential and foundational the Ten Commandments are in Jesus’ teaching. Consider the Sermon on the Mount, a few verses after Jesus saying that He is come to fulfil the Law and the Prophets, where Jesus turns to speak about lust:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery.’ But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent has already committed adultery with her in his heart. If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away. For it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. For it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body go into hell.” (Matt. 5. 27-30)

Here we can see the next point that the Westminster Divines highlight in their ‘How to read the Commandments’ section:

… under one sin or duty, all of the same kind are forbidden or commanded; together with all the causes, means, occasions, and appearances thereof, and provocations thereunto.3

But what do they mean? Well, in His teaching on adultery, Jesus makes it abundantly clear that the Commandment’s prohibition of adultery (#7) does not just refer to the physical act of but instead goes far deeper. A person has committed adultery if he has so much as looked at another person with lustful intent. Although lust is not adultery in itself, it is a sin “of the same kind”4 to remember the Westminster Divines’ wording.

In a similar vain, losing ourselves in the “causes, means, occasions and appearances”5 of the sin is, itself, falling foul of the commandment. Without wanting to focus on any one Commandment in particular (we will have time enough for that in the coming weeks), let’s continue to run with the theme of adultery that Jesus explored. While we all know full well what the physical act of adultery is, what we may not realise is that the Ten Commandments also show us that pornography, the misuse of intimate relationships, flirtatious behaviour and the like are also covered, and also forbidden. Similarly, the occasions, that’s to say, the opportunities to sin, should also be avoided, because of the overarching Commandment. If you are tempted by adult magazines, you would be better not going in to the corner shop that sells them, but instead buying your newspaper from the Co-Op. If you are tempted by online pornography, you’d be better installing parental controls onto your Internet box, and giving the password to someone else. Now of course, these are just examples of actions – not definite instructions – because everyone’s circumstances are different. But the point stands, not only is adultery forbidden, but so too are the occasions or provocations that lead us into it, and the like sins. As Paul says in concluding his first letter to the Thessalonian Church, “Abstain from every form of evil.” (1 Thess. 5. 22, emphasis mine).

Let us return now to the text we heard read, from Exodus itself. And let us pay particular attention to the recipients of the Commandments. I think that, if you’d asked me a few weeks ago, ‘Who did God give the Ten Commandments to?’, I would have answered ‘Moses’. However, if we look in Exodus 19, we can see that (while he had been called up previously), Moses was not alone with God on Mount Sinai when “God spoke all these words”. (Ex. 20. 1) He had gone up in 19. 20, and come down in 19. 25. At the point that God was declaring the Ten Commandments, He was speaking to the whole people of Israel. As David Guzik explains, in his wonderful ‘Enduring Word’ commentary, “It is proper to believe that God spoke these words to Israel as a whole, as they assembled together at the foot of Mount Sinai.”6 Here God was speaking not just to Moses, not just to the Priests, not just to the elite, but to His whole people. These commandments therefore applied to young and old, rich and poor, male and female. The next step in our ‘User Guide’ is to remember that “we are bound, according to our places, to endeavour that [the Commandments are obeyed] by others.”7 Now, of course, this instruction is made clear in the fourth Commandment, where we see that working on the Sabbath day is forbidden both for you (the reader) but also “your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates.” (Ex. 20. 10) It is therefore our duty, as people following the Ten Commandments, to see that we help those around us to follow them too. Now, as the Westminster Divines say, this will look different “according to our places”.8 If you are a parent, your big responsibility will be to help your children follow the Commandments. If you are a husband, it will be helping your wife to follow them. If you are a wife, helping your husband.

The good Scottish Reformation doctrines of the two kingdoms makes it clear that, in the words of the Confession of Faith, “The civil magistrates… hath authority [to ensure] that the truth of God be kept pure and entire, that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed…”.9 Now this may be news to some magistrates(!), but it shows that people in positions of authority are responsible unto God to ensure that those under their care (and control) are helped to follow the laws of God. We can think of some of the great philanthropic businessmen of the 19th century, people like Mr Quaker, Mr Cadbury, Mr Rowntree – people who recognised their responsibilities to their workers above just paying them a reasonable salary. These people created communities which were kept free of the vices that plagued the cities and towns of their time. Even today, in the village of Bournville (created by Mr Cadbury), you cannot buy alcohol10 – it is the only place in the UK where prohibition still exists. And he did this not to be overly controlling (although nowadays people may assume he was a dictator), but because he recognised his Christian responsibility to protect his employees, to safeguard them from the vice of alcoholism. He recognised his responsibility to help his workers follow the Ten Commandments.

We see this theme continued in Leviticus, where we are instructed not to hate our brother, “lest you incur sin because of him”.(Lev. 19. 17) In Genesis we see Abraham instructed to “command his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing righteousness and justice.” (Gen. 18. 19) It is of course worth noting, in Abraham’s case, that this instruction came before the Ten Commandments were even given to mankind – a helpful reminder that the Ten Commandments were not invented on the day Moses and the people received them – they are God’s Law from everlasting to everlasting – but we will cover that later on in the series.

People who come to our home often notice a little brass plaque we have on our front door. Well, actually, we have two: one of them says ‘Topple’, and the other is a quotation from Joshua 24 – “But as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.” (Josh. 24. 15) Here we see that Joshua had made a decision to follow the Lord God, and he recognised his duty to see that his whole household follow the Lord too. As Christians today, as followers of Jesus, we are instructed to ensure that those in our care or charge are not hindered in this walk. Jesus made this abundantly clear where, in Luke’s Gospel, He said, “It would be better for him if a millstone were hung around his neck and he were cast into the sea than that he should cause one of these little ones to sin.” (Luke 17. 2)

This step in our ‘User Guide’, and the next (and final) step, focus on the same thing but approach it in different ways. As Johannes Geerhardus Vos explains:

The general scope of the last two rules is responsibility for the moral welfare of our neighbor. These two rules remind us that righteousness, or obedience to God’s will, is not merely an individual matter but involves a concern for others too. While it is of course true that in the end each individual must give his own account to God, we must remember that part of that accounting will deal with the effect of our lives on the moral well-being of other people.11

This last guide/tip, however, approaches the question from the angle of helping others and/or not partaking in their sin. While the previous tip concerned those who were under our authority, this one feels (to me) more of an instruction concerning our equals. It is this idea that Paul himself expressed when he wrote to the Corinthian Church, and said, “Not that we lord it over your faith, but we work with you for your joy, for you stand firm in your faith.” (2 Cor. 1. 24) Paul could easily have lorded it over the Corinthians – he was, after all, a man sent by Jesus with a great and important mission, but instead he worked with the people to help them with their faith. This could be seen in how we deal with people in our church, in our family, in our work, who are themselves struggling with some sin or difficulty. We must be sure not to be unduly critical, nor “bitter, harsh, or self-righteous”.12 We must remember that, there but for God’s grace, go I.

However, our gentleness must not find itself turned into spiritual malleability. “To participate with others in what is forbidden them is to encourage them in wrongdoing.”13 Paul explains this in his first letter to Timothy, where he instructs the young pastor to not “take part in the sins of others; keep yourself pure.” (1 Tim. 5. 22), and in his letter to the Ephesian Church where he instructs his readers to “Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them.” (Eph. 5. 11)

We’ve all had the temptation, haven’t we. Forbidden fruit, we are told, tastes sweeter. And if someone else has picked it, we are so tempted to be like Adam and eat of Eve’s forbidden fruit. The example Vos gives in his commentary is that of a stolen car. If your friend was to steal a car and go joy-riding, it would not be right for you to accept a ride in the passenger seat. Even if you hadn’t stolen the car yourself, you would be “partaking with others in what is forbidden them.”14

So, friends, in this sermon we have considered what the Catechism calls the “rules… to be observed for the right understanding of the Ten Commandments”.15 I hope you can see how it is only with a “right understanding” that we can even begin to understand the Commandments themselves. While we may have read through the User Guide together, the next time I am here we will begin looking at the spiritual meat – the Commandments themselves. But for now I would encourage you to read through the Ten Commandments together, and ideally read them with these rules or tips in mind, for in so doing we can come together to learn what God would be saying to us through this portion of His holy Word.

Let us pray:

Our gracious Lord God, we thank You for giving us these Commandments to guide our life and encourage us along the paths of righteousness. We repent of those times where we have failed to live according to Your law, those times where we have misused or misunderstood it, and those times where we have forgotten our duties as Christian men and women. We pray that as we continue to explore Your Commandments, we may find ourselves drawn ever closer to You, and Your Son Jesus Christ who came not to abolish the Law, but to fulfil it, accomplishing that which we could never accomplish ourselves. Grant us your grace, we pray, as we read and study Your Word, and continue to lead us as Your flock. For we pray this in Jesus Name. Amen

Works cited:

- Guzik, David. Exodus. Enduring Word Media, 2015.

- Kirby, Dean. ‘Bournville: Trying to Get a Drink in the Village Where Alcohol Has Been Banned for 120 Years’. The Independent, 2 October 2015, sec. Home News. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/bournville-trying-to-get-a-drink-in-the-village-where-alcohol-has-been-banned-for-120-years-a6677551.html.

- Vos, Johannes Geerhardus. The Westminster Larger Catechism : A Commentary. Phillipsburg, N.J. : P&R Pub., 2002. http://archive.org/details/westminsterlarge0000vosj.

- Westminster Divines. ‘The Larger Catechism’. In The Confession of Faith, 49–112. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons Ltd., 1969.

- ———. ‘The Westminster Confession of Faith’. In The Confession of Faith, 49–112. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons Ltd., 1969.

-

Westminster Divines, ‘The Larger Catechism’, in The Confession of Faith (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons Ltd., 1969), sec. 99.4. ↩

-

Ibid., sec. 99.5. ↩

-

Ibid., sec. 99.6. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

David Guzik, Exodus (Enduring Word Media, 2015), chap. 20. ↩

-

Westminster Divines, ‘Larger Catechism’, sec. 99.7. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Westminster Divines, ‘The Westminster Confession of Faith’, in The Confession of Faith (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons Ltd., 1969), chap. 23. 3. ↩

-

Dean Kirby, ‘Bournville: Trying to Get a Drink in the Village Where Alcohol Has Been Banned for 120 Years’, The Independent, 2 October 2015, sec. Home News, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/bournville-trying-to-get-a-drink-in-the-village-where-alcohol-has-been-banned-for-120-years-a6677551.html. ↩

-

Johannes Geerhardus Vos, The Westminster Larger Catechism : A Commentary (Phillipsburg, N.J. : P&R Pub., 2002), 252, http://archive.org/details/westminsterlarge0000vosj. ↩

-

Ibid., 254. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Westminster Divines, ‘Larger Catechism’, sec. 99.8. ↩

-

Ibid., sec 99. ↩